A groundbreaking image compression format called Spectral JPEG XL promises to revolutionize how scientists and engineers work with specialized images that capture light beyond what human eyes can see.

Intel researchers Alban Fichet and Christoph Peters recently unveiled this new format in the Journal of Computer Graphics Techniques, addressing a major challenge in scientific visualization and computer graphics.

While standard digital photos store just red, green and blue (RGB) color data, spectral images capture light intensity across dozens or hundreds of specific wavelength bands, including invisible ultraviolet and infrared light. This detailed data helps scientists analyze everything from paint colors to ancient manuscripts, but creates enormous multi-gigabyte files that are difficult to work with.

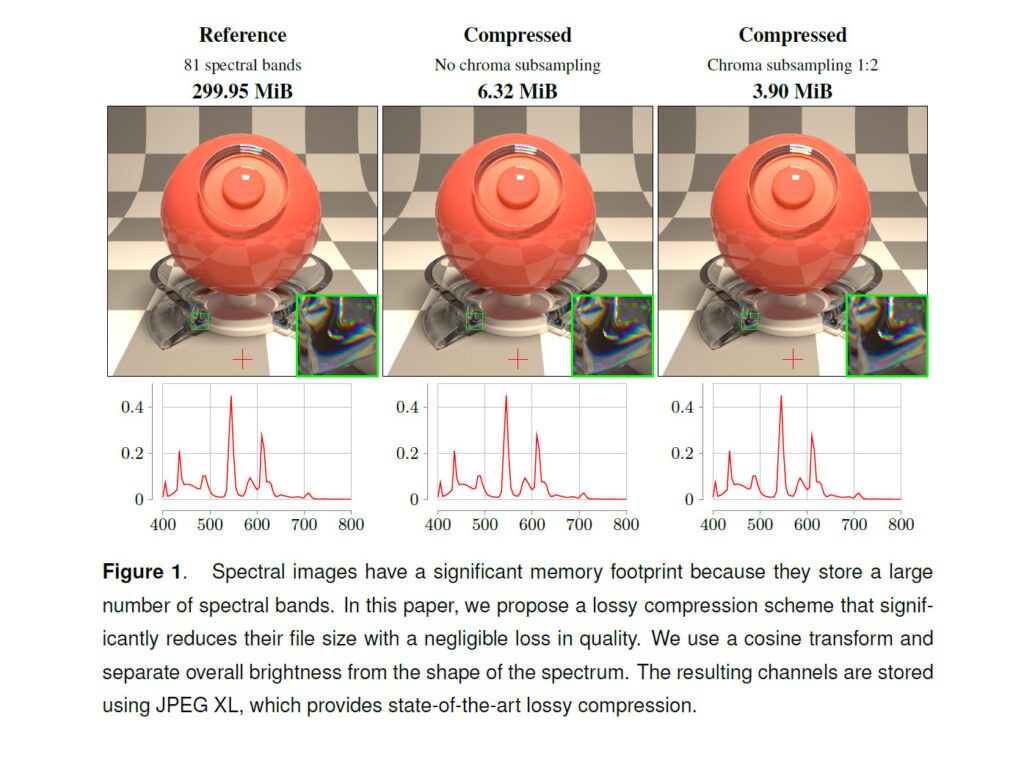

The new Spectral JPEG XL format dramatically reduces these file sizes by 10-60 times compared to current standards, making them comparable to regular high-quality photos. It achieves this through clever mathematical techniques that transform wavelength data into more compressible patterns while preserving the most important visual information.

"This development could remove a major barrier for industries that need spectral imaging but have struggled with the massive file sizes," explained the researchers. The format maintains support for critical features like high dynamic range and metadata.

The compression method finds practical applications across multiple fields:

- Automotive manufacturers analyzing paint appearance

- Scientists identifying materials through light signatures

- Rendering specialists simulating optical effects

- Astronomers studying chemical compositions

- Historians uncovering hidden text in ancient documents

While the lossy compression may not suit every scientific application requiring perfect precision, the dramatic file size reduction makes spectral imaging much more practical for many uses. The format builds on the standardized JPEG XL specification, though software tools for working with it are still under development.

As industries continue generating larger spectral datasets for specialized imaging applications, this new compression technique could help make working with invisible light data as manageable as regular photography.